Last Updated:

Staying out of the electoral sphere allows Jarange to maintain the freedom to critique policies, pressure the government, and inspire grassroots support without navigating the trade-offs that come with legislative duties

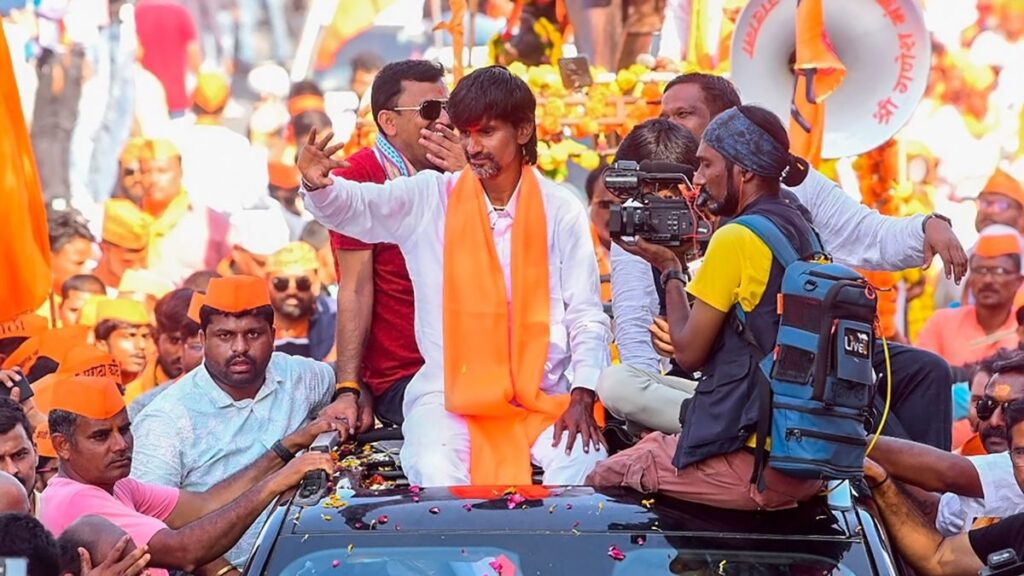

For a figure as central to the Maratha movement as Manoj Jarange, running for office could pose a risk of diluting his message and compromising his effectiveness. (PTI)

Manoj Jarange, an activist who became a powerful advocate for Maratha reservation, has chosen to withdraw from the upcoming Maharashtra assembly elections.

Initially expected to run as an independent candidate, Jarange was seen as a significant contender with the potential to mobilise strong support from the Maratha community, particularly in rural areas. His unexpected exit, however, signals a deliberate and strategic decision focused on preserving the integrity and momentum of the Maratha reservation movement.

Jarange’s choice goes beyond a personal decision — it underscores a focused commitment to an influential movement, reflecting a broader approach to political engagement that’s independent of electoral ambition.

Over the years, Jarange has emerged as a major voice in the Maratha community, leading their demands for reservation with unwavering focus. The Maratha quota issue is both socioeconomically and politically sensitive in Maharashtra, with a large section of the community advocating for reserved access to government jobs and educational opportunities. Various governments have attempted to introduce reservation for Marathas, only to face judicial pushback due to constitutional restrictions. This ongoing struggle has, over time, become both a rallying point and a source of frustration within the community.

By withdrawing from the electoral race, Jarange aims to keep his focus solely on the Maratha quota fight rather than diverting energy into legislative responsibilities. He has emphasised that his work and influence are more effective outside the structured bounds of the assembly, enabling him to act as a vocal critic or ally to any government, based on their stance on Maratha rights. His decision is therefore a calculated one, positioning him as a leader who prioritises community advancement over personal political aspirations.

For a figure as central to the Maratha movement as Jarange, running for office could pose a risk of diluting his message and compromising his effectiveness. As an elected official, he would inevitably be part of a party apparatus or coalition, potentially reducing his freedom to challenge policies or advocate forcefully for the Maratha community’s demands. Additionally, the pressures of office, political compromise, and daily governance could lessen his standing as an independent advocate, binding him to the limitations and responsibilities of office.

By staying out of the electoral sphere, Jarange avoids these constraints. His position outside the system allows him to maintain the freedom to critique policies, pressure the government, and inspire grassroots support without navigating the trade-offs that come with legislative duties. This approach helps retain his influence as a leader who serves as a voice for his community without allegiance to any political entity, an important aspect in a movement seeking systemic, long-term change.

Jarange’s decision to withdraw from the elections will influence the strategies of Maharashtra’s major political players as they vie for the Maratha vote bank. The Maratha vote, historically diverse in its loyalties, has shown tendencies to support parties perceived as sympathetic to their cause. However, the reservation issue remains a significant determinant of support, and political parties have a vested interest in appealing to this sizeable voting bloc.

For the ruling government, Jarange’s absence may sidestep direct conflict with a highly popular independent candidate. However, his continued advocacy will still hold the government accountable for its actions on the Maratha reservation issue. With Jarange out of the race, the ruling Mahayuti may feel temporarily relieved but should be aware that his influence as a vocal critic will persist, especially if their approach to Maratha demands appears inadequate.

Conversely, the opposition parties, particularly the Congress, Shiv Sena UBT and NCP combine also known as Maha Vikas Aghadi, may see this as an opportunity to leverage Jarange’s decision to critique the government’s handling of the quota issue. The Opposition could argue that the government’s inaction or lack of effective policy has sidelined the Maratha cause, potentially appealing to Maratha voters by promising to prioritise reservation if elected.

In this way, Jarange’s choice not to run has opened a unique space within the political discourse, providing opposition parties with a lever to use in their campaign narratives. Also, Jarange, who is continuously targeting Devendra Fadnavis despite the government being led by Eknath Shinde, will certainly campaign against BJP and its candidates.

In the recently held Lok Sabha elections, though Jarange did not field any candidate, his style of campaigning led to the MVA gaining success in the Marathwada region where BJP bigwigs, including Pankaja Munde, had to face defeat due consolidation of Maratha votes against BJP.

Since then, BJP is trying to appease OBCs in the state by introducing various schemes. According to political analysts, BJP’s attempts to consolidate OBC votes may again fuel the Maratha community to consolidate against the Mahayuti alliance, giving an edge to MVA.

Another significant outcome of Jarange’s decision is the continued pressure it places on the Maharashtra government. The Maratha quota issue has long been a point of contention, and successive administrations have struggled to find a lasting solution.

Jarange’s refusal to participate in the election keeps the reservation issue alive and active in public discourse, with the potential to influence the electoral platforms of all major parties. His focus on advocacy rather than electoral office sends a message to the state’s political establishment: the Maratha reservation movement is not simply a campaign issue, but an enduring social demand that politicians must address to gain long-term support from the Maratha community.

This is particularly pertinent as the state faces other caste-based demands for reservation, such as those from the OBC community, requiring the government to balance multiple constituencies with competing interests. By opting out of the assembly race, Jarange reinforces the Maratha movement’s focus on systemic reform over political gain. This could potentially reshape the Maratha community’s approach to reservation, broadening the movement to incorporate related issues such as educational access, economic opportunities, and rural development.

The movement could now push for a more comprehensive policy framework aimed at socio-economic upliftment, emphasising the need for structural improvements that extend beyond reservation alone.

In choosing not to contest the Maharashtra assembly elections, Jarange has made a strategic decision that underscores his commitment to the Maratha reservation cause. By remaining outside the political arena, he retains his ability to act as an independent watchdog for the Maratha community, unencumbered by the limitations of political office. His absence from the electoral race signals a message to political parties: the Maratha reservation movement will persist and cannot be co-opted or diluted by temporary promises.

This move has broader implications for Maharashtra’s politics, possibly leading to renewed activism and empowering local leaders to advance the reservation issue. Jarange’s choice to stay out of electoral politics is a reminder that some movements achieve strength through non-electoral pathways, reinforcing the message that real change may require committed, independent advocacy rather than legislative representation alone.